Quantum mechanics and machine learning

Quantum mechanics (QM), the theory of matter at atomic scale, allows calculation of virtually any property of a molecule or material. However, accurate numerical procedures scale as high-order polynomials in system size, preventing applications to large systems, long time scales, or big data sets. Machine learning (ML) provides algorithms that identify non-linear relationships in large high-dimensional data sets via induction. Our research focuses on models that combine QM with ML. These QM/ML models use ML to interpolate between QM reference calculations, yielding speed-ups of up to several orders of magnitude when the same QM procedure is carried out for a large number of similar inputs, e.g., in virtual screening, molecular dynamics, or self-consistent field calculations. We are particularly interested in models that generalize across chemical compound space.

-

M. Rupp, A. Tkatchenko, K.-R. Müller, O.A. von Lilienfeld: Fast and Accurate Modeling of Molecular Atomization Energies with Machine Learning, Physical Review Letters 108(5): 058301, 2012. [doi] [pdf]

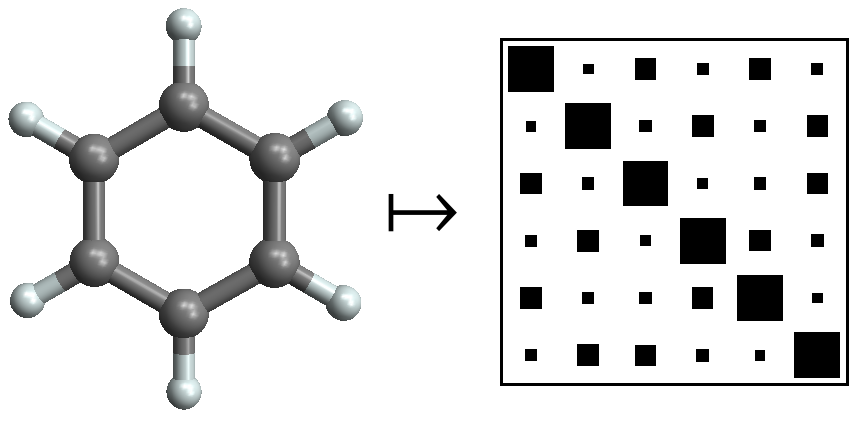

We use machine learning to predict DFT atomization energies of a diverse set of 7k small organic molecules with an accuracy of 10 kcal/mol, introducing the Coulomb matrix representation to compare different molecules. In follow-up studies, we extend our approach to different properties at various levels of theories, analyzing datasets as large as 134k molecules, and achieving accuracies below 1 kcal/mol.

-

- J.C. Snyder, M. Rupp, K. Hansen, L. Blooston, K.-R. Müller, K. Burke: Orbital-free Bond Breaking via Machine Learning, Journal of Chemical Physics, 139(22): 224104, 2013. [doi] [pdf]

- J.C. Snyder, M. Rupp, K. Hansen, K.-R. Müller, K. Burke: Finding Density Functionals with Machine Learning, Physical Review Letters 108(25): 253002, 2012. [doi] [pdf]

Machine learning is used to estimate the map from electron densities to their kinetic energy in a one-dimensional model potential. With few reference calculations, errors are smaller than typical errors of many exchange-correlation functionals. In follow-up studies, we introduce non-linear gradient denoising to find highly accurate self-consistent densities, successfully dissociating chemical bonds.